Written on the Walls: Kaiser Graffiti just another form of student expression

November 26, 2022

During recent months, graffiti has become relatively prominent in the halls of Kaiser High School, perhaps presenting a vague description of student opinion.

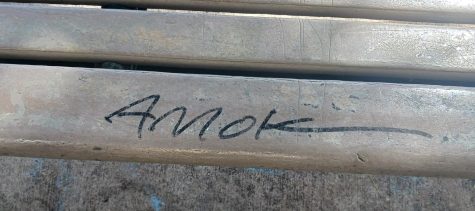

The graffiti spans from derogatory phrases that insult the DOE to pleasant reminders to have a good day. The most intriguing, however, seems to be the single words drawn across school tiles with obscure, even unknown, meanings. “Astro” (sometimes Astro 15) has slowly traced the walls of Hawaii Kai and reaches closer to school grounds while “AMOK” (having originated inside the school campus) has been traced all the way to bus stops near school grounds, bringing to light another aspect of student expression, however unclear it may be at this time.

(Photo credit: Kailani Clark)

Whether or not graffiti is a form of expression has been a topic of debate for years. The controversial art form sparks discussion over property lines and permission. The first “writer,” Cornbread, was found in Philadelphia in 1967. Tagging and scratching later moved to New York in the 70s and 80s, covering the windows of subway cars and the underbellies of city bridges.

People debate the difference between artistic expression and vandalism by bringing up theories of marked territory and tying graffiti to increased crime rates. As for Hawaii, ‘graffiti’ isn’t so prevalent as vibrant street art such as the famous intercultural political murals in Kaka’ako. Less publicized tags are present all around the island, but none so concerning to add national debates of crime rates.

(Photo credit: Kailani Clark)

However, the essential definition of “graffiti” is a visual art form. And what is art but communication?

From the perspective of a tagger themself, graffiti, however innocent, inevitably reaches the definition of a statement. “I think it’s a form of art… Everybody’s perception of what’s good and bad differs. To me, it’s just art… But any form of art can be used as a statement piece.”

This particular tagger uses the name Vilin, drawn with an arrow, developed after two years of practice. As with beginner custom, Vilin initially copied the prevalent Astro tags (originally Astro 15) along the walls of K- Highway and some bus stops around Hawaii Kai. But so as not to breach the line between admiration and theft of an artist’s work, they created their own tag and use it sporadically around school and town.

“When you’re all trying to get away with the same scheme, you kind of bump into each other… More commonly it’s duos. But there’s a lot of people who want to do it by themselves. And then there’s the groups which range from five to ten people.”

Anonymity does not run far in local communities, but unspoken rules of discretion keep any identities from reaching authorities. “There’s kind of a rule where there are no snitches… The whole community has no idea who Astro 15 is which is very impressive because it’s hard to stay anonymous when there are places that everyone goes to… We all kinda know who Amok is but nobody’s going to say.”

As for the definition, to run amok is widely known as “behaving uncontrollably and disruptively.” But ‘amok’ alone yields a heavier, though similar, definition: “in a murderously and frenzied state.” Raging, wild, uncontrolled. The artist uses the word alone, leaving us to question their intent. A description; insulting or objective? For society or the individual?

According to Vilin, while most tag names do carry a certain amount of personality and representation, Amok does not mean anything so ominous by their tag. “My tag is definitely a statement to myself… I guess to an extent we’re all kind of villains… But I have no idea what Amok means. I have no idea if there is or isn’t a meaning, I’m not sure.”

On the topic of illegality, while Vilin does perceive the prejudice against graffiti to be rather uninformed, they do recognize the line between art and vandalism. “If you’re going to somebody’s house, somebody’s property, and drawing on the wall, that is vandalism. When you’re taking advantage of someone else’s property. But public property, which is where most ‘vandalism’ takes place, it’s a public area.” Vilin questions the difference between vandalism and art as the definition in different people’s eyes. “What’s the difference?”

“In a way, graffiti is a form of making a statement. It also turns into kind of a political thing. ‘Is it raising crime rates? Is it affecting children in the area?’ I think, to an extent, it is a political thing. But, in that same breath, it’s still art.”

‘Tagging’ is widely known to mark territory. In other parts of the world (even the island), it is commonly related to gang communication. But in Hawaii Kai and around Kaiser (with no gang activity), Vilin claims it to be looser marks of personality rather than territory. If any boundaries are being breached, it is between schools. “Majority of the time, the community is just artists supporting artists. But sometimes, it’s a territory thing. People from outside the community will come in and black out our work to cover it with theirs… It’s really petty. Like, ‘I’m better than you.’”

“It really is personal… It doesn’t help that, since there are no snitches and a lot of us know each other like we put a face to a name, it can become an actual problem where they have a problem with the actual person attached to the tag… At that point, it becomes personal… It’s just drama between taggers.”

However, Vilin also recognizes a decline in blackouts around town as administration reduces the opportunities for them. Most of the AMOK symbols and other prominent markings have been speedily covered around campus as it is, after all, illegal to mark public property. “The school is painting over it. Nobody even gets the opportunity to black each other’s art out… Especially the campus beautification team. They be painting over it all the time.”

“We hate that the administration wants to cover it… School administration has been putting out more and more stops… They’re installing more security cameras…The campus beautification team goes out every week. They put a gate on the second-floor weight room.”

Amok, Vilin, the approaching Astro to school grounds. Taggers in Hawaii Kai mean no harm, claims Vilin. “In my opinion, if it’s okay for us to put graffiti on the walls in the art hall, it should be ok for us to put it anywhere. Because it’s a representation of who we are as students, who we are as people. Just because the school perceives it to be ugly, that does not apply to us. We consider it to be art.”

The tension between Kaiser taggers and administration is straining, but the writers show no intention of giving up their post, though they are reducing the amount of work they put up.

(Photo credit: Kailani Clark)

“I know the majority take it personally because it’s a representation of them outside of their name. It’s a way of anonymously expressing themselves… If your personal name is attached, people perceive it differently. But when it’s a name that you came up with, with that significant meaning, it’s your art form on the wall, nobody has any preconceived notions about you. It’s different. It’s a feeling that nobody can describe.”

For many writers, there is more clarity in anonymity. With no bias in the way, transparency becomes automatic and a tag name on the wall is purely oneself.

Its initial presence, however temporary, leaves an underlying subconscious amongst the students themselves. It brings to question the controversy in artistic endeavors, the difference between truth in temporary art and statements in personal tags. Perhaps reading too far into things is tedious itself. But on the other hand, should any further disturbances come to light, let it be known that the thoughts of some were written on the walls.

(Photo credit: Kailani Clark)